Madness & Taxes In The 27th Kingdom

Alice Thomas Ellis, The 27th Kingdom, 1982

|

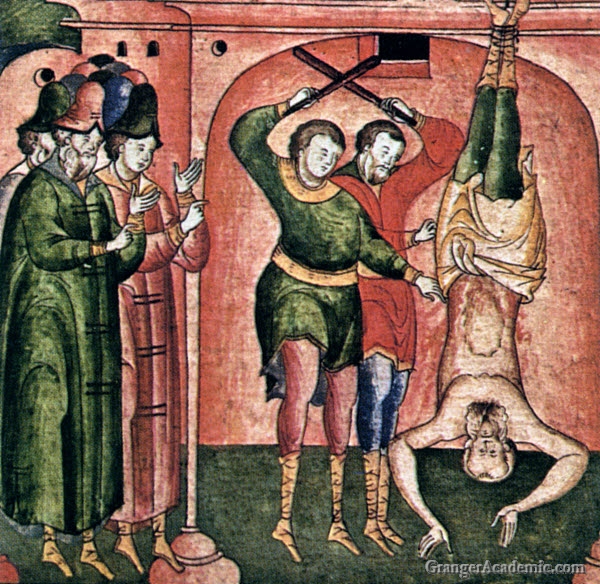

| C16th manuscript illumination |

Have you ever had a difference of opinion with the Taxman, Dear Reader? It is a tiresome affair. But one can be grateful that we're not under the C14th reign of Ivan I, Prince of Moscow and Grand Prince Vladimir, whereupon tax collectors took a rather more hands-on approach to extracting pesos from reluctant subjects for their Sovereign overlord, as is fetchingly illuminated above.

But at some point, the tables must have turned even in Russia, as Aunt Irene, hailing from a family of Roman Catholic émigrés who fled from that hallowed homeland across lands and countries and is presently finding herself at odds with the Inland Revenue in the 27th Kingdom, reflects:

Some minor official had been persecuting her for months with trivial enquiries about her means; but since she couldn't bear forms and had a profound conviction that her need of her own money was greater than the government's, she had ignored him. She felt the noble irritation of a fine spirit called from viewing the sunset to inspect the blockage in the kitchen sink. Her ancestors, she thought, would have him boiled. In oil.

I suspect that a general survey across most Kingdoms today would find that Taxmen operate somewhere betwixt the thrashing of subjects and being themselves boiled in oil. While for the taxpayer, these outgoings are still an affliction to be borne like madness.

Aunt Irene went through the various forms of tragedy that afflict the living: madness and death duties for the upper classes, hunger and indignity for the lower, the eldest son's marriage to the girl on the haberdashery counter for the middle.

Warm and generous Aunt Irene, who presides over her cosy dominion in 1954 Chelsea, finds plenty with which to philosophise further in Alice Thomas Ellis's little gem of a 1982 Booker-Prize-shortlisted novel, The 27th Kingdom.

"'Why are you looking like that?' asked Kyril.'I was wondering why people put ferrets in their trousers,' said Aunt Irene.

'Thanatos,' said Kyril. 'An illustration of the death wish.'

'What I wish,' said Aunt Irene, 'is that you'd never read Freud. It's had a very leaden effect on your conversation.'"

|

| The Ferret Thomas Bewick wood engraving, 1790 |

As you may guess, this book finds natural endorsement by the Flying With Hands Department of Whimsy for its light and fanciful touch, as opposed to the withering review I found by a New York Times reviewer (bandying about such words as cocksure, facetious, smirky, tired, done to death - phooey! and one who evidently cannot enjoy 150-odd pages of slightly mad company.) Kyril, by the way, is the odious nephew of Aunt Irene and rather considers himself irresistible for both his beauty and his charming wisdom:

"'He's one of those people,' said Kyril, 'who once they go into analysis never never come out - which wouldn't matter if they'd keep it to themselves, but then they never talk about anything else. It gets to be a way of life, and they become extremely earnest and keep examining their motives and looking straight into other people's eyes, and yakking on about transference and ambivalence and complexes until you could murder them. It renders them entirely unfit for human society.'"

It is into her bohemian yet genteel home, Dancing Master House, that Aunt Irene (whose "own looks had gone - disappeared under waves of creamy, curdling flesh. How odd that bones, reminders of old mortality, should be considered essential to beauty in this perverse age") takes in a luminous, Caribbean postulant, Valentine. And the assembled cast of lodger (sad Little Mr. Sirocco) and Kyril's tormented lovers, char-women Mrs. Mason (fallen on hard times and resentful) and Mrs. O'Connor (with the shady side-hustles and jolly), and a cat with more sense than most of them has a mysterious new member.

Valentine it seems, has been sent by Irene's sister, the Mother Superior of a Welsh convent, to rub shoulders with the earthly and hopefully lose some of her unsettling, slightly saintly qualities. For in amongst the still pocked, post-war landscape of London there is plenty of space for a thaumaturge to float relatively unnoticed among the mortal and venial sinners, and take the pressure off the quiet convent.

_MET_costanzi.jpg) |

| Thaumaturgy in action, or A Miracle of Saint Joseph of Cupertino Placido Costanzi, 1750 |

But it's not all sweetness and light in this slight, supernatural tale. Times are hard and housing is still short. The recent war has left its scars on the city and its people, and opportunists abound. "There was, thought Aunt Irene, a glaring thread of madness in human affairs which shed about it a short, confounding light towards which people were drawn like death-drugged gnats."

Not to mention that lurking tax man. After a worrying visit from him, Aunt Irene is served a restorative cup of tooth-stripping tea in her own good china by the jollier of her charwomen, Mrs. O'Connor. "The world was upside down. On the whole this pleased Aunt Irene as much as it angered Mrs Mason. It was more interesting that way, but it was hard on the porcelain."

Image credits: 1: GrangerAcademic.com; 2: Flying With Hands; 3: V&A Museum; 4: Wikimedia Commons

[First Published on Flying With Hands, April 2021]